1st part – until 2015

Manu Lafer composes the first level of popular Brazilian songs. I consider his production extremely competent and varied. And fruitful: over one hundred songs released, with about four times that composed. If you have still to experience his talent, now is a good time. Here, I present a selection of the songs I consider most representative of the artist born in São Paulo, in 1971.

Since Baião da Flor (1998), there have been nine albums he has authored, one with Danilo Caymmi and another, with Mateus Aleluia, in addition to the DVD A Lente do Homem (2008). There are also two albums he interpreted: Someone Like You (2014) and, again with Mateus Aleluia, Como Tu Ninguém (2015).

The songs collected, here, are mainly the ones I enjoy the best from his songbook. They are separated by album, which were ordered by release date. I will point out if the composition was a partnership. This is a panoramic and personal presentation. An introduction. A listening guide.

Manu Lafer

Manu Lafer’s musical education was mainly influenced by Luiz Tatit, from whom he learned guitar and who would later become his partner in composing Versão Fiel. He also studied the guitar with Cezar Mendes Nogueira (the nephew and disciple of Paulinho Nogueira) and Ítalo Perón. His singing teachers were Ná Ozzetti, Fernanda Gianesella and Wagner Barbosa (a specialist in speech level singing).

Among his composing partners, Danilo Caymmi is the most recurrent one. He partnered directly with him and the aforementioned Tatit, in addition to Dori Caymmi, Fábio Tagliaferri, Guilherme Wisnik, Alexandre Barbosa de Souza and Bruno Cara, among others. Meanwhile, indirectly, as it were, he partnered with John Pizzarelli and Jessica Molaskey, for whom he penned a version of Perfect Afternoon, a song they authored.

Lafer’s albums were collaborated on by some of the most prestigious arrangers in Brazil, with his most extensive collaboration being with Lincoln Olivetti (with whom he worked for 11 years, resulting in two full albums). Jacques Morelenbaum, Luiz Brasil, Dori Caymmi, André Mehmari and Jetter Garotti Jr are other arrangers who wrote for Lafer’s albums.

These albums had renowned music producers, most notably the award-winning Alê Siqueira, involved in almost the entirety of Lafer’s discography and whose classical formation at Instituto de Artes da UNESP still echoes in the depth of his productions and arrangements. The DVD A Lente do Homem, Lafer’s first live recording, was produced by Déo Teixeira. Swami Júnior (Omara Portuondo) and Fabio Tagliaferri produced another CD.

Lafer has been sung by famous interpreters, such as Nana Caymmi, Ná Ozzetti, Mateus Aleluia, Germano Mathias, Mônica Salmaso, Cris Aflalo and José Miguel Wisnik, among others.

The listening (and reading) guide

Listening to all the albums is the best way for you, on your own, to comprehend the songbook of Manu Lafer, but you might want or need a faster option. Hence, the reason for this guide: to offer you five options to (begin to) get to know this authorial discography.

If you want to start with a song or two, my suggestion is to listen and read about:

Se optar começar por um álbum, comece pelo:

1. Cidade Inacabada (5’): the most representative of the distinctive qualities of his songs;

2. Ta Shemá (3’): if Lafer were a song, it would be Ta Shemá;

If you decide on an album, start with:

3. Ta Shemá: if Lafer were an album, it would be this one (60’).

However, if you prefer to begin with a brief overview, listen to:

4. The main pick from each album(50’).

Or, if your preference is for an encompassing overview, your selection is:

5. Four songs from each album, including the main picks (one per album) plus another three songs suggested per album (150’)

I will now delve deeper into each of these options.

By album, one main pick and three other suggestions

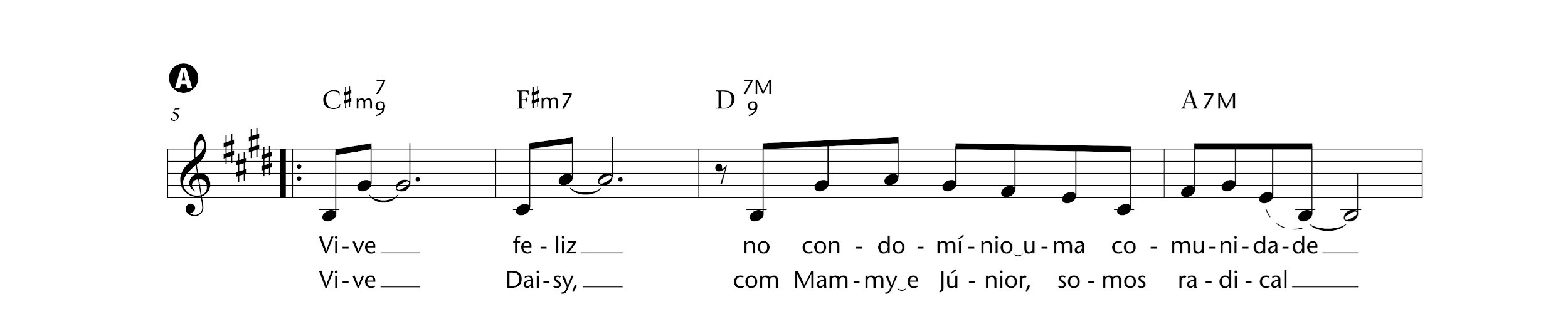

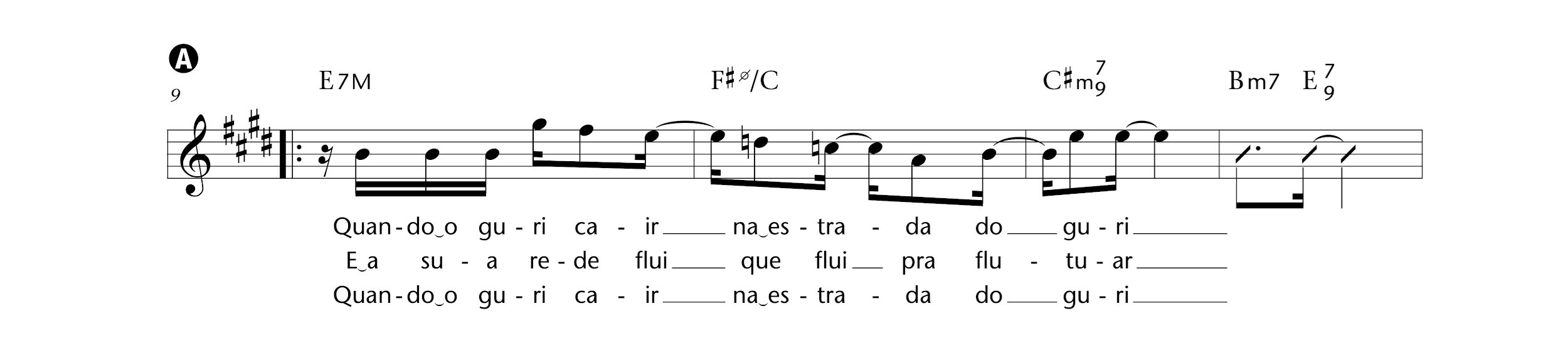

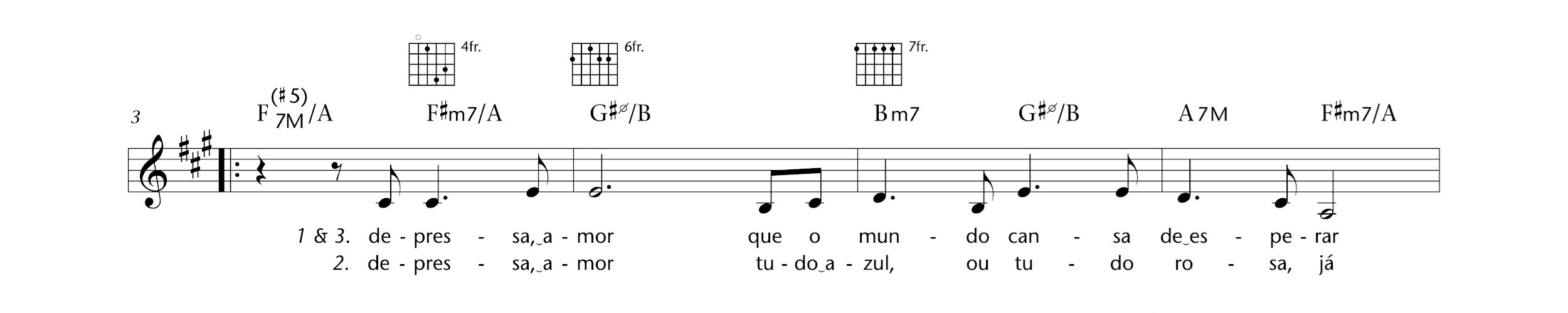

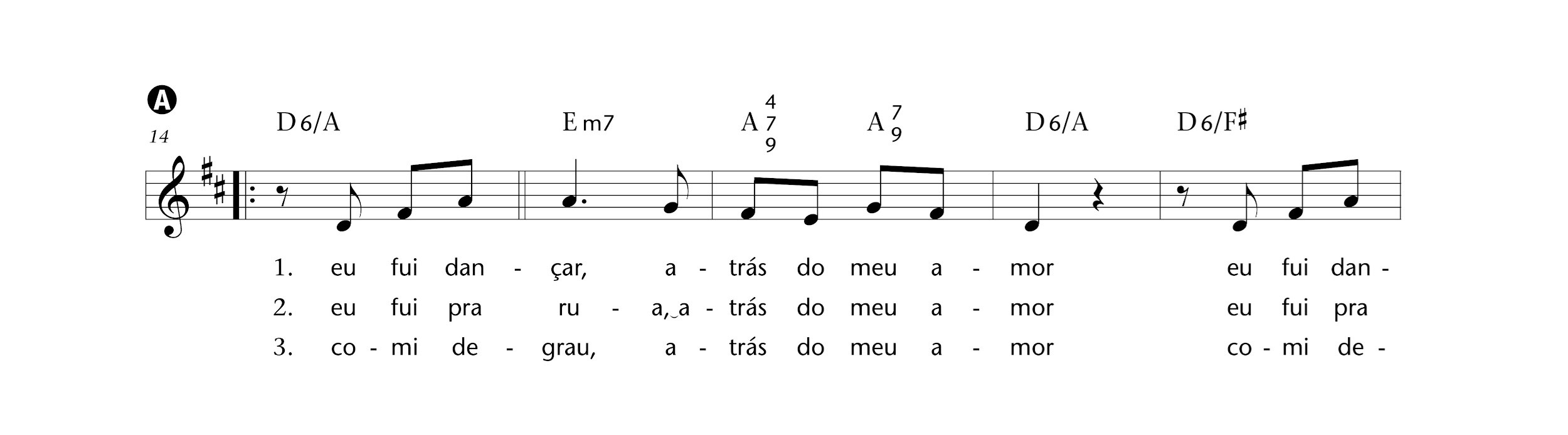

Depressa Amor [Hurry, Love]

Depressa, amor [Hurry, love]

Que o mundo cansa [For the world grows weary]

De esperar [Of waiting]

Depressa, amor [Hurry, love]

Veja a vida [See life]

Não como ela está [Not as it is]

Depressa, [Hurry,]

Que é você quem vai chegar [For it is you who will arrive]

Depressa, [Hurry,]

Que sei quem você será [For I know who you will be]

Depressa, amor [Hurry, love]

Tudo azul, [All blue,]

Ou tudo rosa já [Or all pink by now]

Depressa, amor [Hurry, love]

Preto e branco [Black and white]

Só se for filmar [Only if it’s filmed]

Depressa, [Hurry,]

Que é tempo de passar [For it’s time to pass]

O tempo desse mundo [The time of this world]

Quem sonhar [For those who dream]

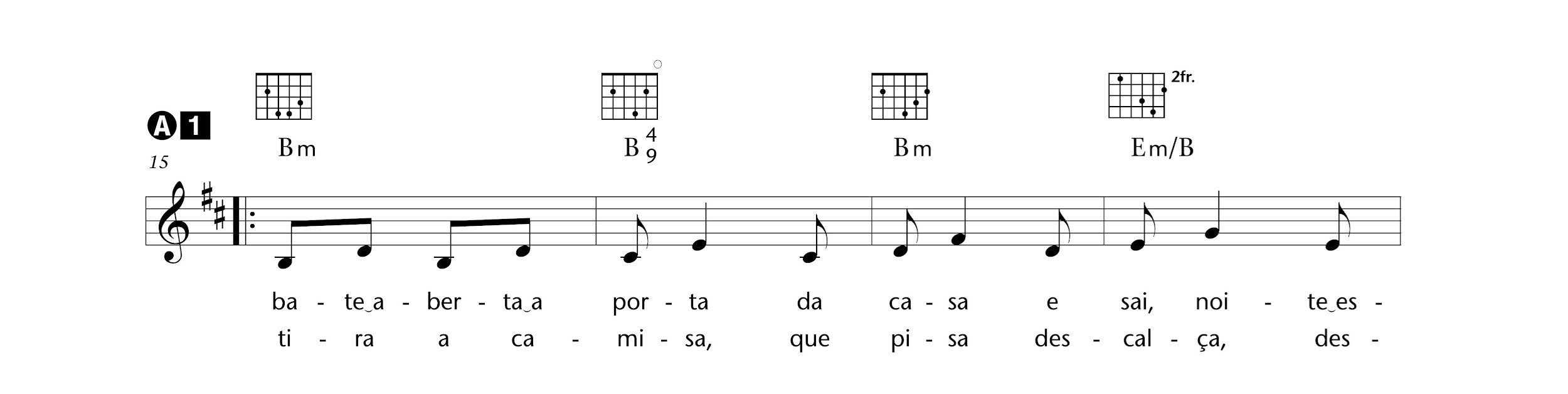

Present in the album Baião da Flor (1988), the only one released under his maternal surname, Mindlin, Depressa Amor is beautifully sung by Ná Ozzetti (1958). It is characterized by the subject of the lyrics being in stark opposition to the music’s soothing nature. The music is calm, while the subject in the lyrics sings of the hurry that may be needed in reclaiming a love. This dialogue of natures, in this case, diverging ones, was raised to a singular level by Robert Schumann (1810-1856) in his lieder. The harmony and accompaniment remind us of Gymnopedie, by Erik Satie (1866–1965) and has an unusual rhythm from Lafer’s songbook. Formally, the vocals are sectioned into two parts and are embraced by the instrumental cadence of the introduction and its final reappearance. The introduction and coda contain the chromaticism typical of samba songs, like Carinhoso and Aquarela do Brasil, which links this song to the songbook of Brazil, and especially Cidade Inacabada, a song by the composer himself.

More highlights from the album Baião da Flor (for this and the remaining albums, the highlights are presented in track order, not order of preference):

- Eu Vou Te Pegar

- Nascimento

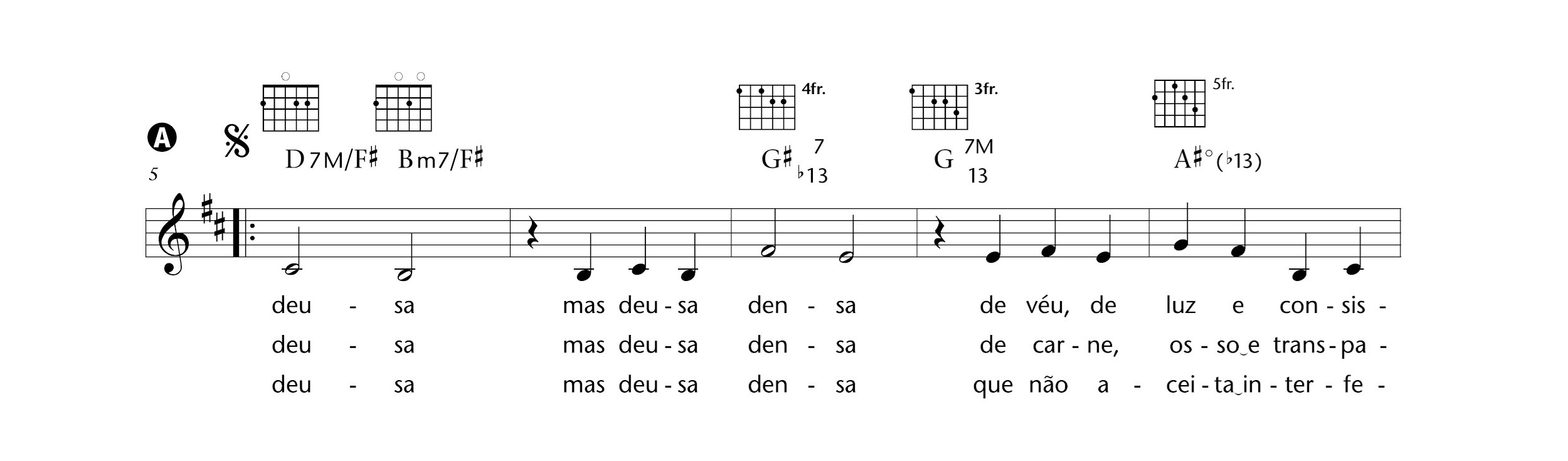

- Deusa Densa

A Lente do Homem [Man’s Lens]

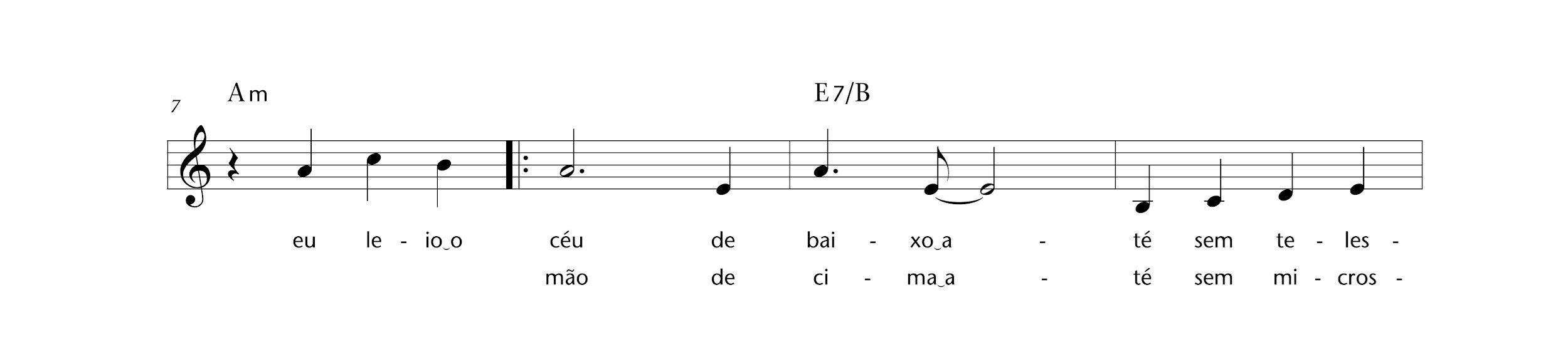

Eu leio o céu de baixo [I read the bottom sky]

Até sem telescópio [Even without a telescope]

É que o céu sou eu [It’s because the sky is me]

Porque o céu é um ser [Because the sky is a person]

Eu leio a mão de cima [I read the top hand]

Até sem microscópio [Even without a microscope]

É que a mão é Deus [It’s because the hand is God]

Porque a mão é um ser [Because the hand is a person]

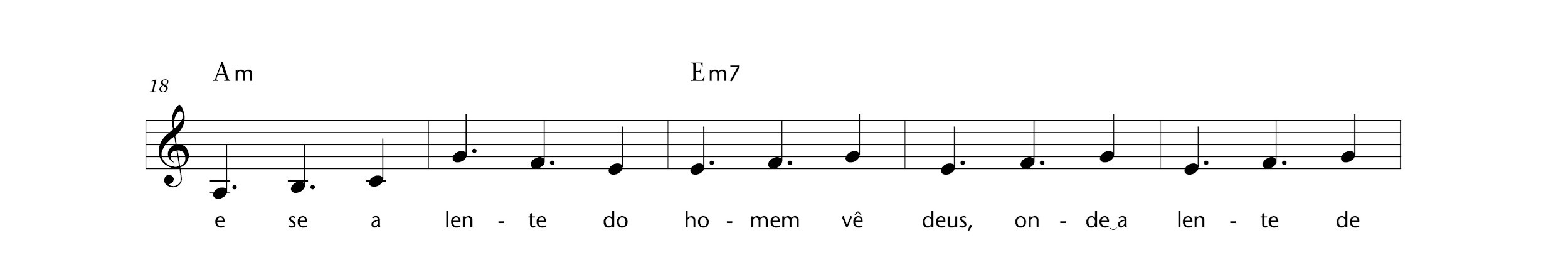

E se a lente do homem [And if Man’s lens]

Vê Deus, onde a lente [Sees God, where the lens]

De Deus vê o homem [Of God sees Man]

Saber é a imagem da fé [Knowledge is the image of faith]

Que do outro se crê [Which of the other is believed]

E se do núcleo da célula [And if from the nucleus of the cell]

A íris espelha o destino [The iris mirrors the destiny]

O dilema: ou a morte [ The dilemma: or death]

Ou o bom, e o belo, e o dom [Or the good, and the beautiful, and the gift]

Eu leio o céu de baixo [I read the bottom sky]

Até sem telescópio [Even without a telescope]

É que o céu sou eu [It’s because the sky is me]

Porque o céu é um ser [Because the sky is a person]

Eu leio a mão de cima [I read the top hand]

Até sem microscópio [Even without a microscope]

É que a mão é Deus [It’s because the hand is God]

Porque a mão é um ser [Because the hand is a person]

E se o amor é a fé [And if love is faith]

Que do prisma do afeto [Which from the prism of affection]

É o fim que é o feto [Is the end that is the fetus]

Onde o ventre é o teto [Where the womb is the ceiling]

Que o tato tocou [That the touch contacted]

E porque há sinfonia [It’s because there is symphony]

Há também harmonia, [There is also harmony,]

Há também melodia [There is also melody]

E o dia, e o ‘ia’, e o ‘a’ que criou [And the “ony” and the “ny” and the “y” that created]

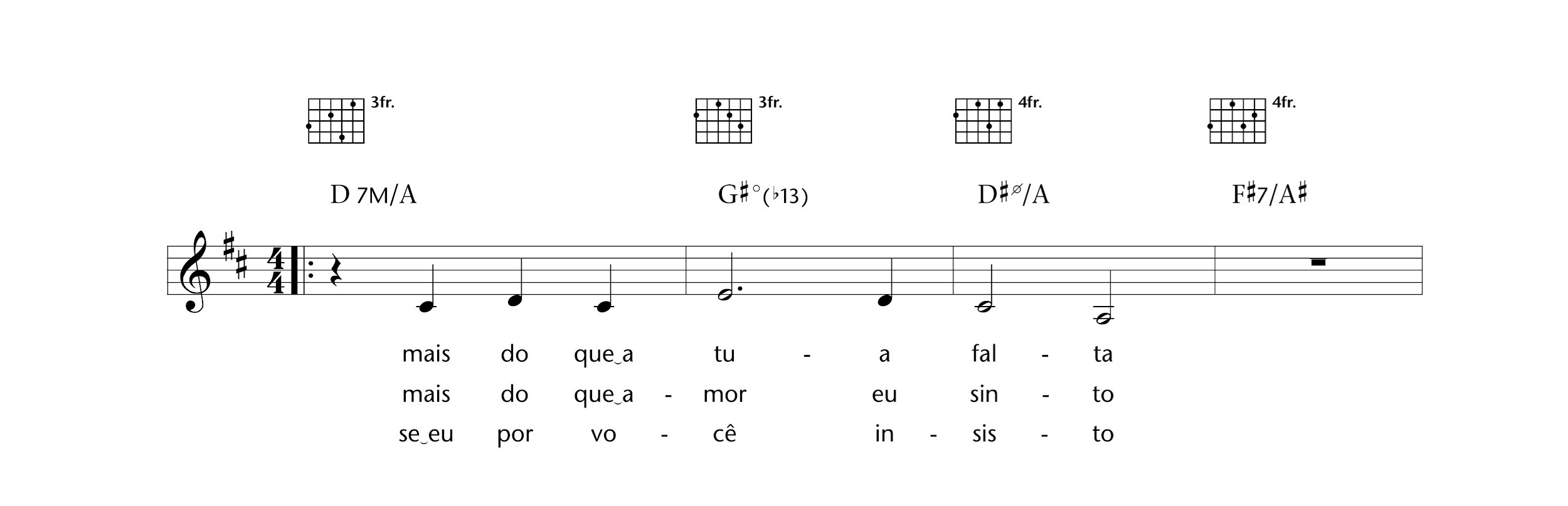

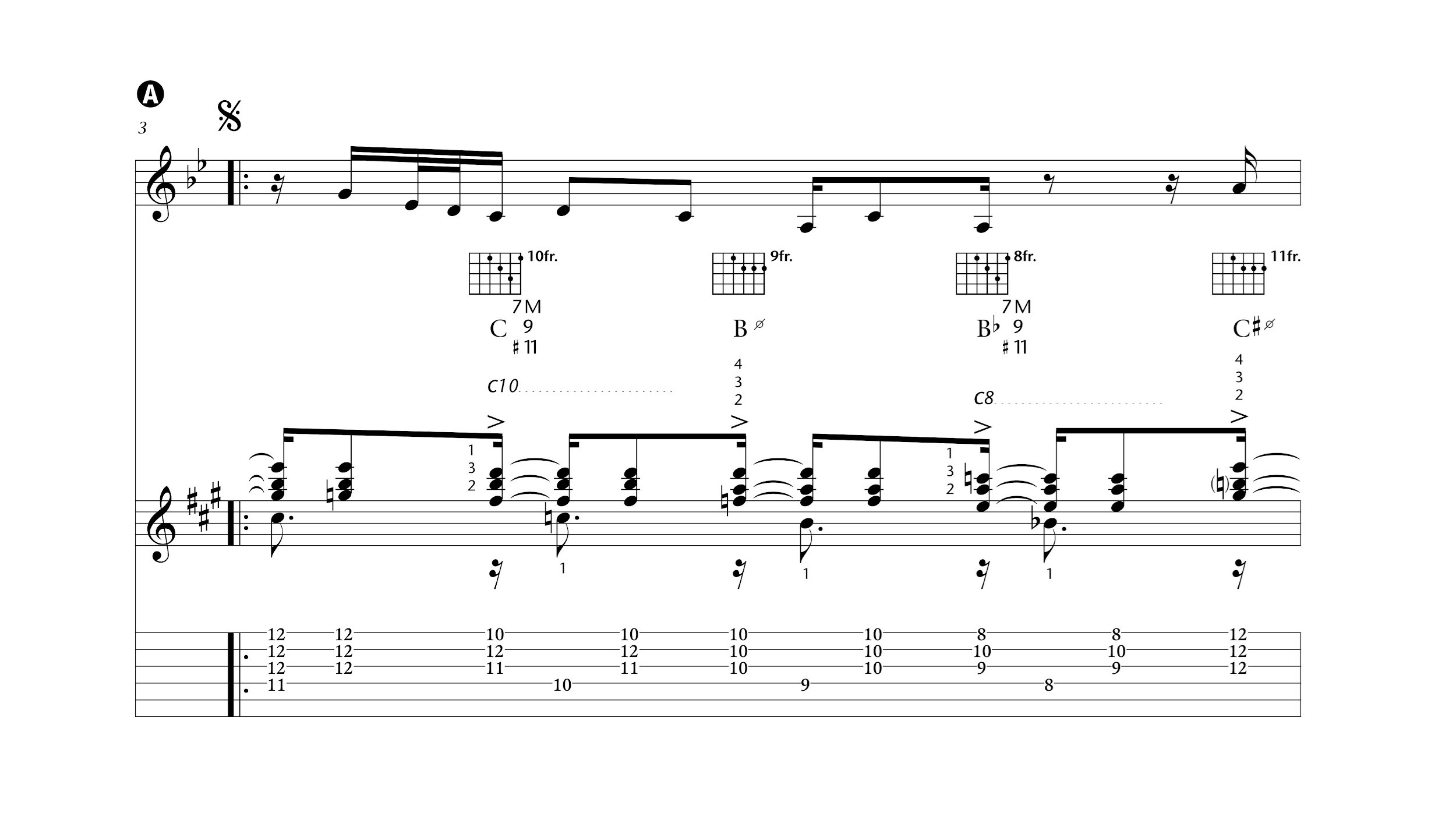

A song that tends to pique immediate interest, A Lente do Homem was released in the album Doze Fotogramas (2001), which contains thirteen songs, not a dozen. Doze Fotogramas is also the title of another song in this album. This kind of “playful riddle”, of “trickster’s cadence”, is one of the characteristics present in A Lente do Homem and in the artist’s work; the quotes come from an article I wrote about another song from this album, Cidade Inacabada, which I consider one of his best two songs, together with (at the time, unreleased) Afeto Santo. From this album, A Lente do Homem is the most remembered and recognized, partly because it was also sung and recorded by big names from Brazilian popular music, such as: Mônica Salmaso, who recorded it in Doze Fotogramas; Ná Ozzetti, who recorded it in her own album Embalar (2013); Mateus Aleluia, who recorded it in Cinco Sentidos (2010) , and Cris Aflalo, who recorded it, in 2008, in the Live DVD that shares its title with the song and was Lafer’s first album recorded live.

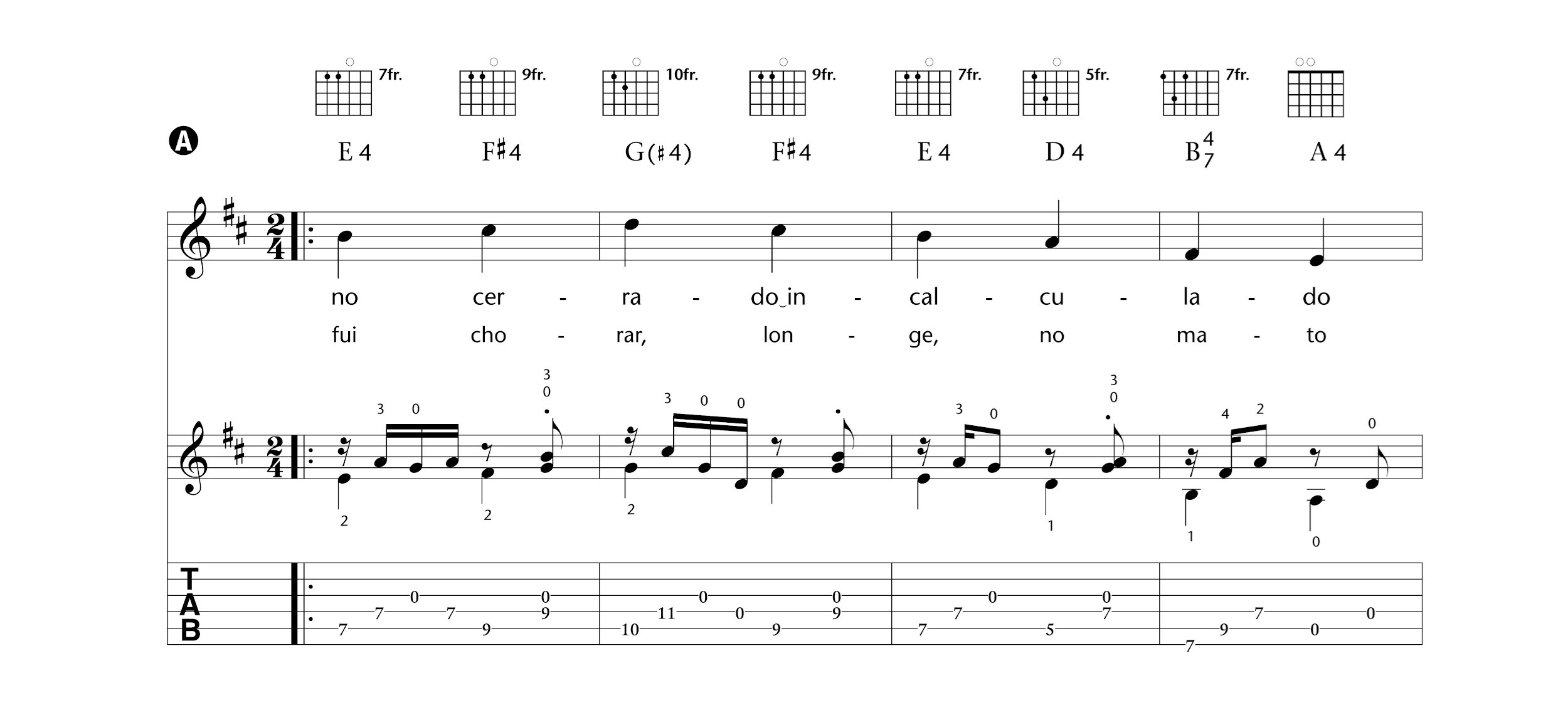

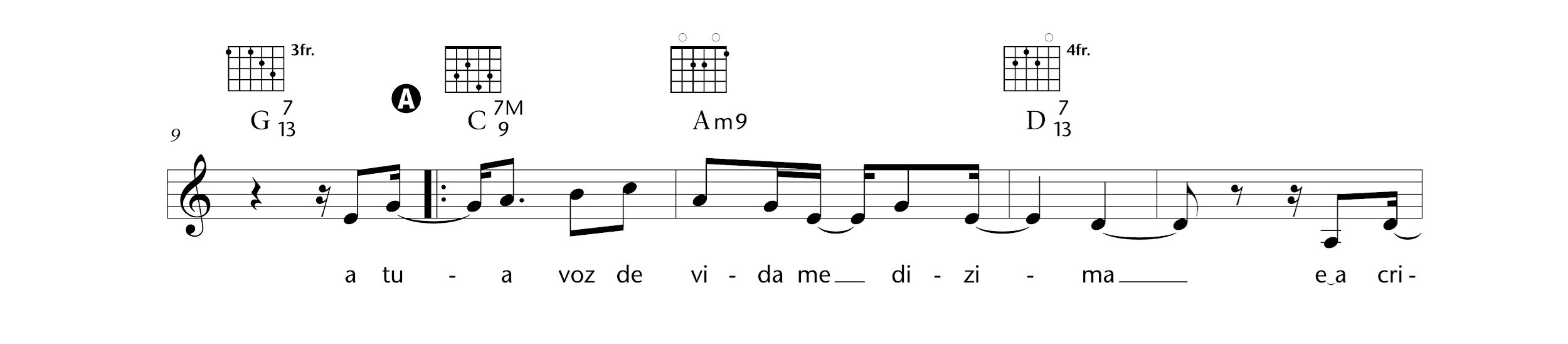

The subject in the lyrics raises an ontological question: when dealing with man and Man, who sees who and how? How much is seen and how much is interpreted? It is a poetic version of ancestral questions. And a contemporary one, as attested to by the discussion raised by the Higgs Boson. I believe it is fair to focus on the text, the melody greatly simplifies the rhythmic division, reaching the point of becoming perpetual motion, as we can see below.

This rhythmic regularity extends to the accompaniment; it is known in various styles. (In Tango, it is called the three-three-two and proponents of the genre are intimately acquainted with it. Does this explain the arrangers choice of an accordion’s timbre? My bet is it does.) The harmony is also simple, one of the simplest from Lafer’s songbook.

More highlights from the album Doze Fotogramas:

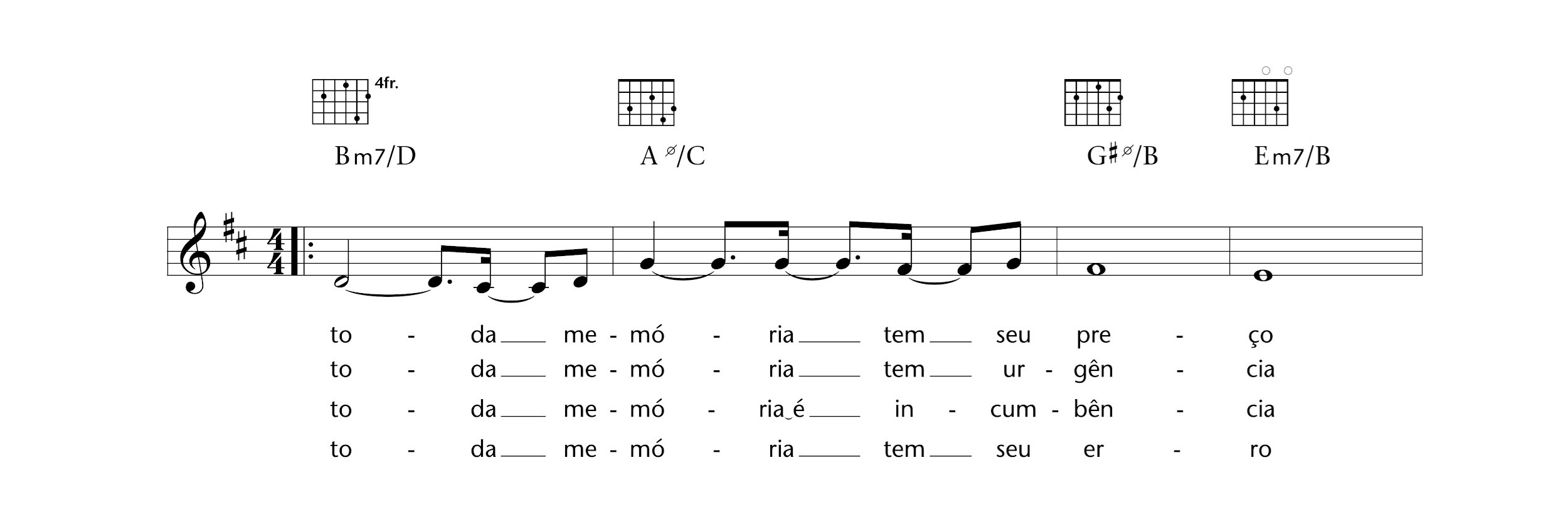

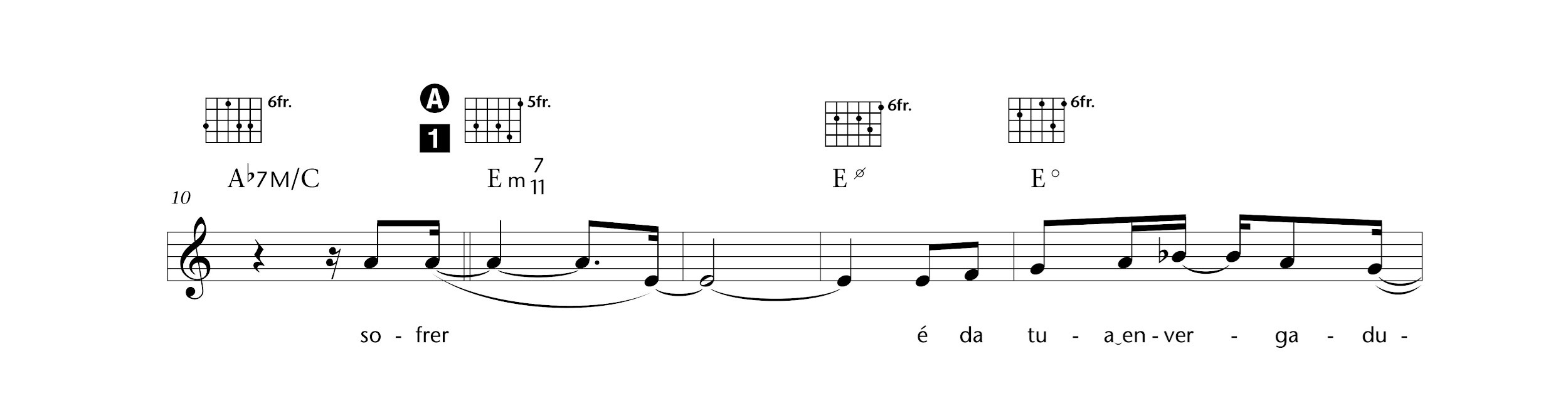

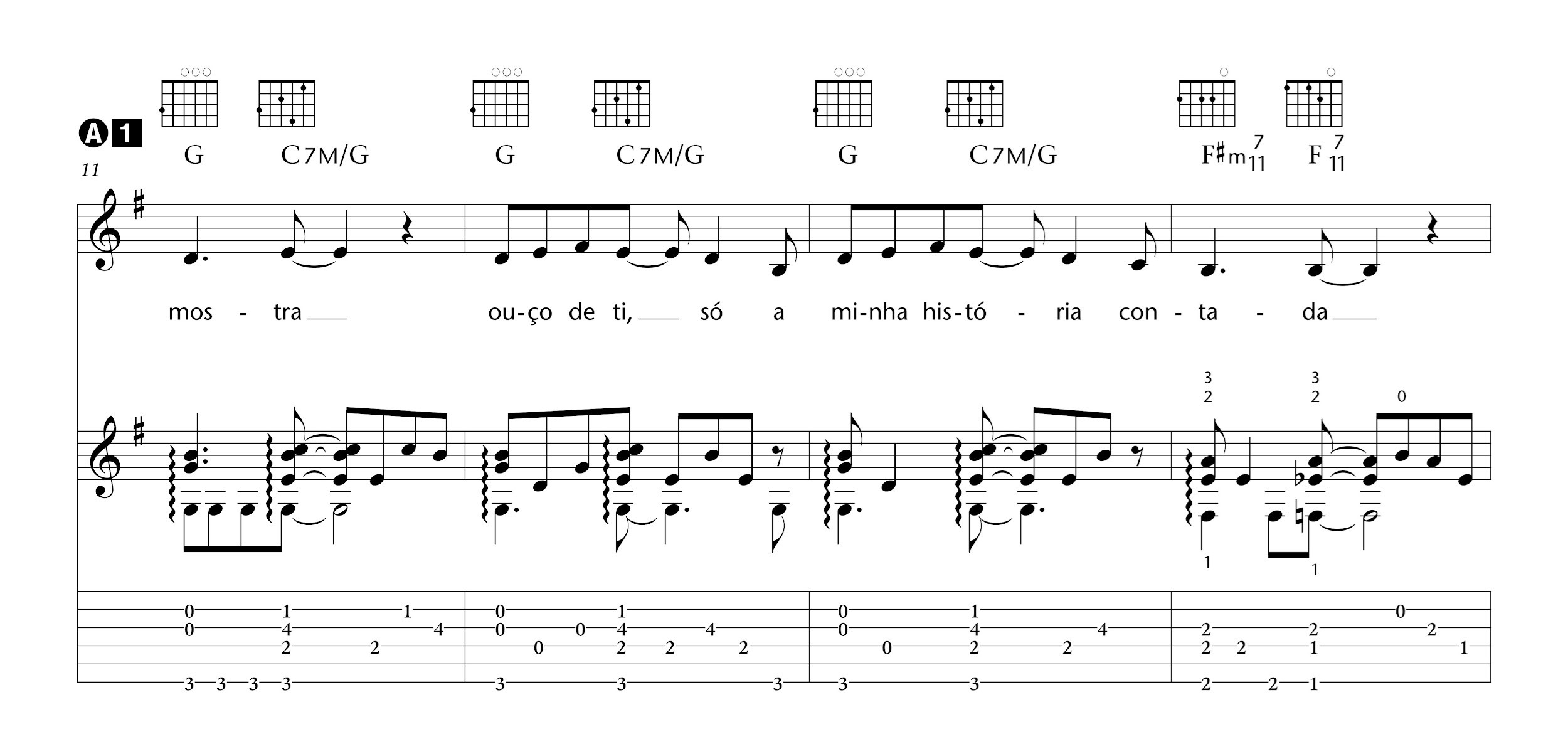

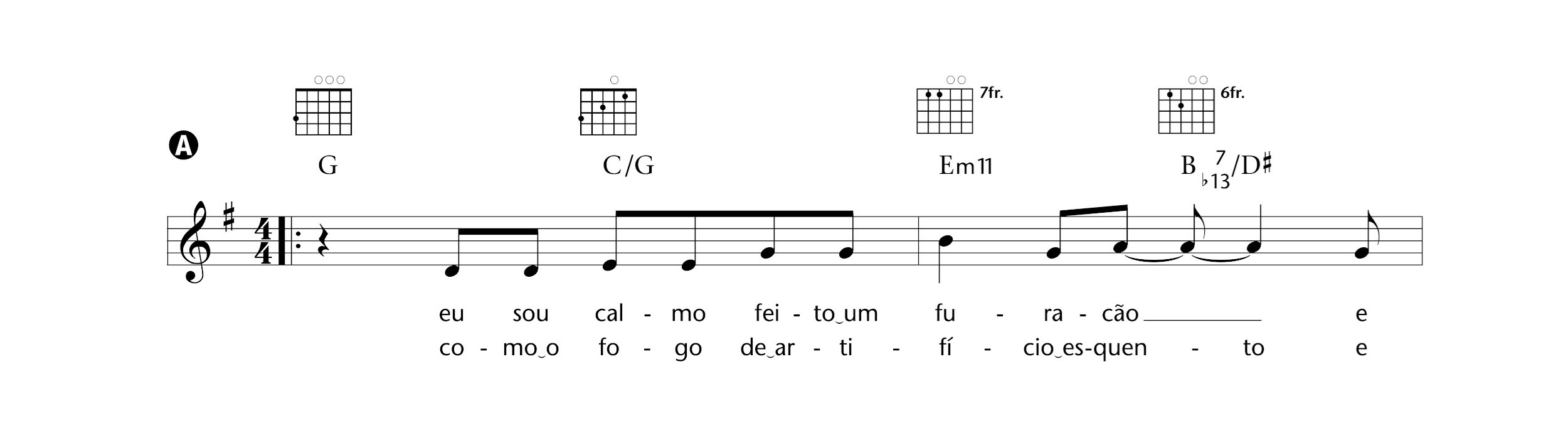

- Memória

- Se Couber

- Cidade Inacabada

Pedir Pra Voltar [Ask to Return]

Gosta? [Like it?]

Faça um poema [Write a poem]

Que tenha a beleza da arte [With the beauty of art]

Falte, com a verdade [Lack, with the truth]

E sem me deixar terminar [And without letting me finish]

Tenho sido tão intenso [I have been so intense]

E tão sofrido [And suffered so much]

Coisa estranha [A strange thing]

O meu sorriso [My smile]

Recupera teu amor [Recovers your love]

Hoje em dia eu sou contido [Nowadays I’m contained]

Sou fiel, arrependido [I’m faithful, regretful]

E só penso “o que passou… [Only thinking “what has passed…]

… passa” [passes”]

Passa pro fim, já [Passes to the end, already]

Para que a graça arrebate [For fun to wash away]

Dar-te, dar-te o destino [Give you, give you destiny]

Esse é meu hino [That is my hymn]

E não mais [And no longer is]

(esse é meu hino e não mais) [(that is my hymn and no longer is)]

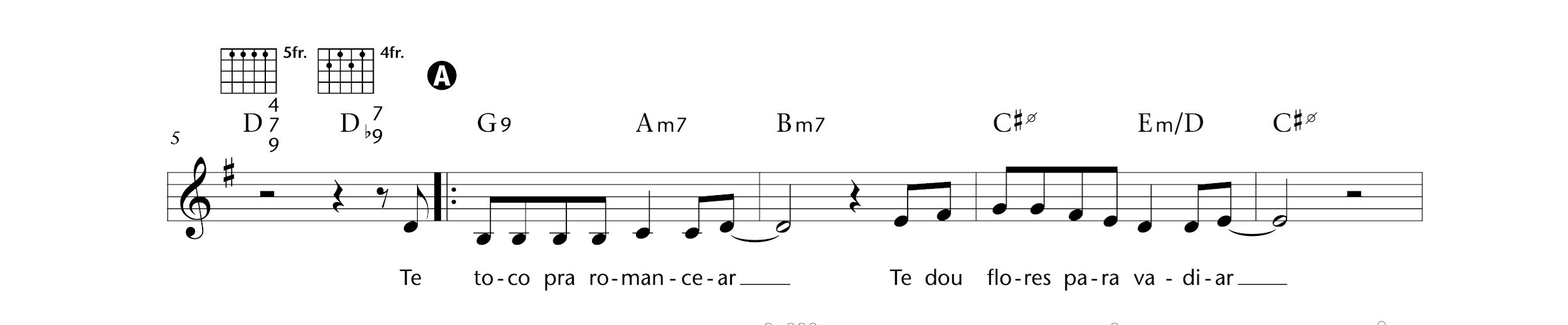

Released in the album O Patriota (2002), where each song was authored together with his most recurrent composing partner, Danilo Caymmi (1948-), Pedir Pra Voltar is a song by brothers Danilo and Dori Caymmi (1943) (the latter played the beautiful guitar part of the arrangement) and lyrics by Lafer.

As in some of his other songs, the rhythm accompanies the formal division of the music. Here, parts A (the first, second and fourth verses, but especially the first two) are focused around phonemes with the vowel “a”, with or without the stress; and in part B (the third verse), used as the chorus, the lyrics are focused on phonemes with “i”, where it is stressed. The last appearance of part A makes use of both phonemes, as if it were liquidating and concluding sonorous elements where the letter is based – in Portuguese, examples would include passa, graça, dar-te, destino, hino. Harmonically, the music is simple; nevertheless it fulfills: A1 and A2 in G major; B1 in the relative tonic, B minor; B2 in the mediating upper B major; and A3 returns to G major. The original song was sung by Nana Caymmi (1941).

More highlights from the album O Patriota (all three by Lafer and Danilo Caymmi):

- Cândido

- Insônia

- Tangorel

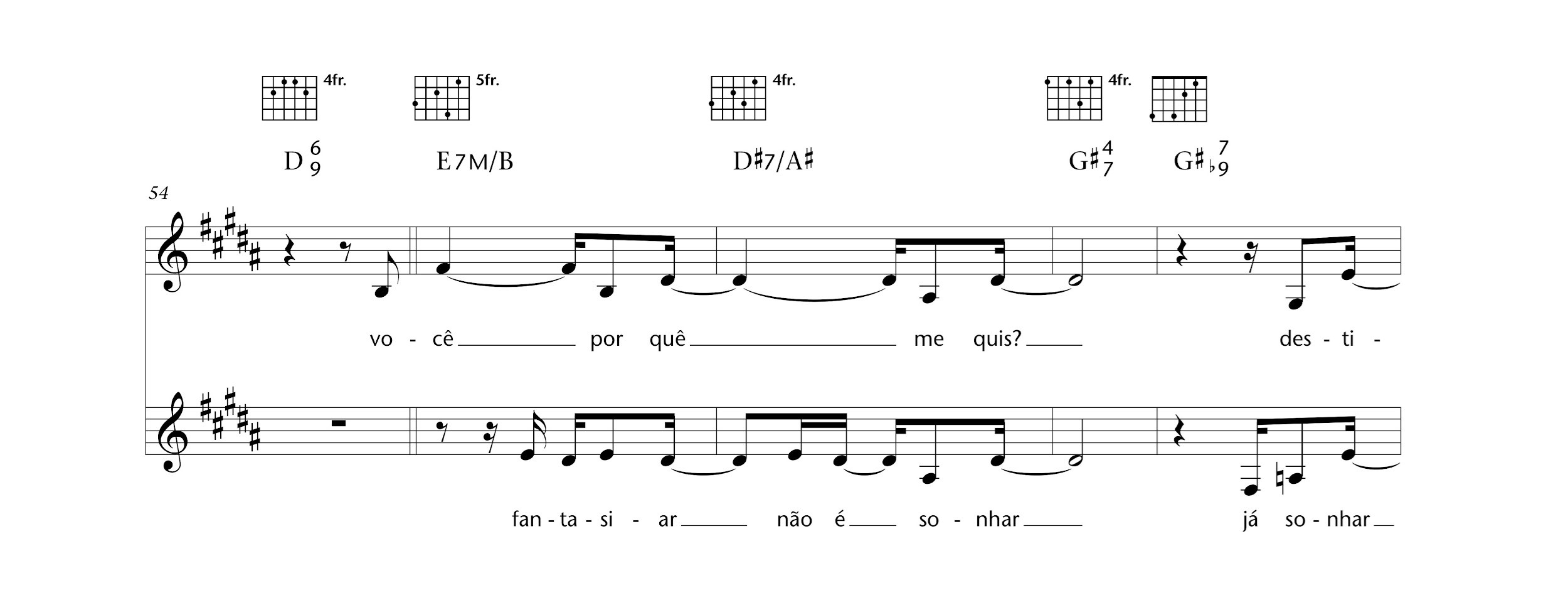

Com Fantasia [With Fantasy]

Fantasiar não é sonhar [Fantasizing is not dreaming]

Já sonhar [But dreaming]

É a noite acabando [Is the night ending]

Não é pra crer, [It’s not to believe,]

Nem é pra ter [Nor to have]

Faça tudo agora [Do it all now]

Para mim, [For me]

Na madrugada, [In the dawn,]

Sem porquê [No reason why]

Você vai acontecer [You will happen]

Eu não quero amanhecer [I don’t want morning to come]

Porque eu te quero [Because I want you]

E nada mais [And nothing else]

Você [You]

Por quê me quis? [Why didn’t you want me?]

Destino? [Destiny?]

Vida? [Life?]

Fala! [Speak!]

Você vai jurar [You will swear]

Deixar de sonhar [Dream no longer]

Não é você. [It isn’t you.]

Só nós dois [Only we two]

Sabemos [Know]

O que nos fazemos [What we do]

Para a madrugada [For dawn]

Acordar mais tarde [To break later]

A duet since its conception, Com Fantasia is part of the album Grandeza (2006), in which Agda Sardenberg (19??) sings with Lafer. The song is a clear reference to Sem Fantasia, by Chico Buarque (1944) and with which it creates a dialogue, if not responding to it. Buarque wrote it in 1967, for the play Roda Viva.

Vem, meu menino vadio [Come to me, my naughty boy]

Vem, sem mentir pra você [Come, without lying to you]

Vem, mas vem sem fantasia [Come, but without fantasy]

Que da noite pro dia [Because from night to day]

Você não vai crescer [You won’t grow]

Vem, por favor não evites [Come, please don’t avoid]

Meu amor, meus convites [My love, my invitations]

Minha dor, meus apelos [My pain, my appeals]

Vou te envolver nos cabelos [I will enfold you in my hair]

Vem perder-te em meus braços [Come lose yourself in my arms]

Pelo amor de Deus [For the love of God]

Vem que eu te quero fraco [Come because I want you weak]

Vem que eu te quero tolo [Come because I want you foolish]

Vem que eu te quero todo meu [Come because I want you just for me]

Ah, eu quero te dizer [Oh, I want to tell you]

Que o instante de te ver [That the moment I see you]

Custou tanto penar [Cost me so much pain]

Não vou me arrepender [I won’t regret it]

Só vim te convencer [I just came to convince you]

Que eu vim pra não morrer [That I came to not die]

De tanto te esperar [From waiting for you so long]

Eu quero te contar [I want to tell you]

Das chuvas que apanhei [Of the rain I collected]

Das noites que varei [Of the nights I stayed up]

No escuro a te buscar [In the dark, searching for you]

Eu quero te mostrar [I want to show you]

As marcas que ganhei [The marks I earned]

Nas lutas contra o rei [In the fights against the king]

Nas discussões com Deus [In the arguments with God]

E agora que cheguei [And now that I arrived]

Eu quero a recompensa [I want the reward]

Eu quero a prenda imensa [I want the greatest gift]

Dos carinhos teus [Of your caresses]

Both are descendents of Samba em Prelúdio, by Baden Powell (1937–2000) and Vinícius de Moraes (1913–1980). Ultimately, they derive from short, baroque operas known as operettas, a word not used disparagingly.

Eu sem você não tenho porque [Me without you has no reason why]

Porque sem você não sei nem chorar [Because without you I can’t even cry]

Sou chama sem luz [I am a flame without light]

Jardim sem luar [A garden without moonlight]

Luar sem amor [Moonlight without love]

Amor sem se dar [Love without giving]

E sem você [And without you]

Sou só desamor [I am just loveless]

Um barco sem mar [A ship with no sea]

Um campo sem flor [A field with no flowers]

Tristeza que vai [Sadness that goes]

Tristeza que vem [Sadness that comes]

Sem você meu amor eu não sou [Without you my love I am not]

Ninguém [Anyone]

Ah, que saudade [Oh, what longing]

Que vontade de ver renascer [What desire to see reborn]

Nossa vida [Our life]

Volta querido [Return dear]

Os meus braços precisam dos teus [My arms need yours]

Teus abraços precisam dos meus [Your hugs need mine]

Estou tão sozinha [I’m so alone]

Tenho os olhos cansados de olhar [My eyes are tired from watching]

Para o além [To the beyond]

Vem ver a vida [Come see life]

Sem você meu amor eu não sou [Without you my love I am not]

Ninguém [Anyone]

Com Fantasia, Sem Fantasia, and Samba em Prelúdio have the same musical form and poetic: all three are A; B; A & B (overlapping). The music, lyrics and vocals all follow them. In the first parts, the first character sings, while the second character sings in the second parts, answering the first. Which is expected. What is unexpected is that there is no solution to the emotional tension, because in the third parts both characters argue in overlap. They become confused. But do not fuse. In love, even when they feel as one, they are liquid and, if the turbulence ceases or they do not transmute into a new, good state, they decant and separate.

More highlights from the album Grandeza:

- Conversa de Japi

- A Dança

- Murundum

Ta Shemá

A alma, o salmo, a flama, a chama, a neshamá [The soul, the psalm, the flame, the neshama]

Ta shemá, ta shemá [Ta shema, ta shema]

A água, a vaga, a frota, a fraga da torá [ The water, the vacancy, the fleet, the boulder of the Torah

Eu quero vir Inês chamar [I want to call Inês]

Os céus dos céus, raquéus [Rachels, skies of the skies]

O leite, o véu, a luz, o lar [The milk, the veil, the light, the home]

Ta shemá, ta shemá [Ta shema, ta shema]

O mês, a vez, o nes, Inês [The month, the time, Inês]

Irmã do mesmo, siamês [Sister of the same, Siamese]

E neste ente inestimar [And in this entity count invaluable]

Vem escutar, após, a mais [Come to listen, after, the most]

O tempo, o topo, o tampo, [Time, the top, the cap,]

A via, as vidas, alegrias [The way, the lives, happiness]

Onde havia algaravia [Where there was gibberish]

O giro, o suspiro, a tocha, [The turn, the sigh, the torch,]

A pira vir a deflagrar [The pyre come to incite]

Soar midrash e sussurrar mishná [Sound midrash and whisper Mishnah]

Que era e haverá antes [What was and will be before]

Das vogais errantes [ The errant vowels]

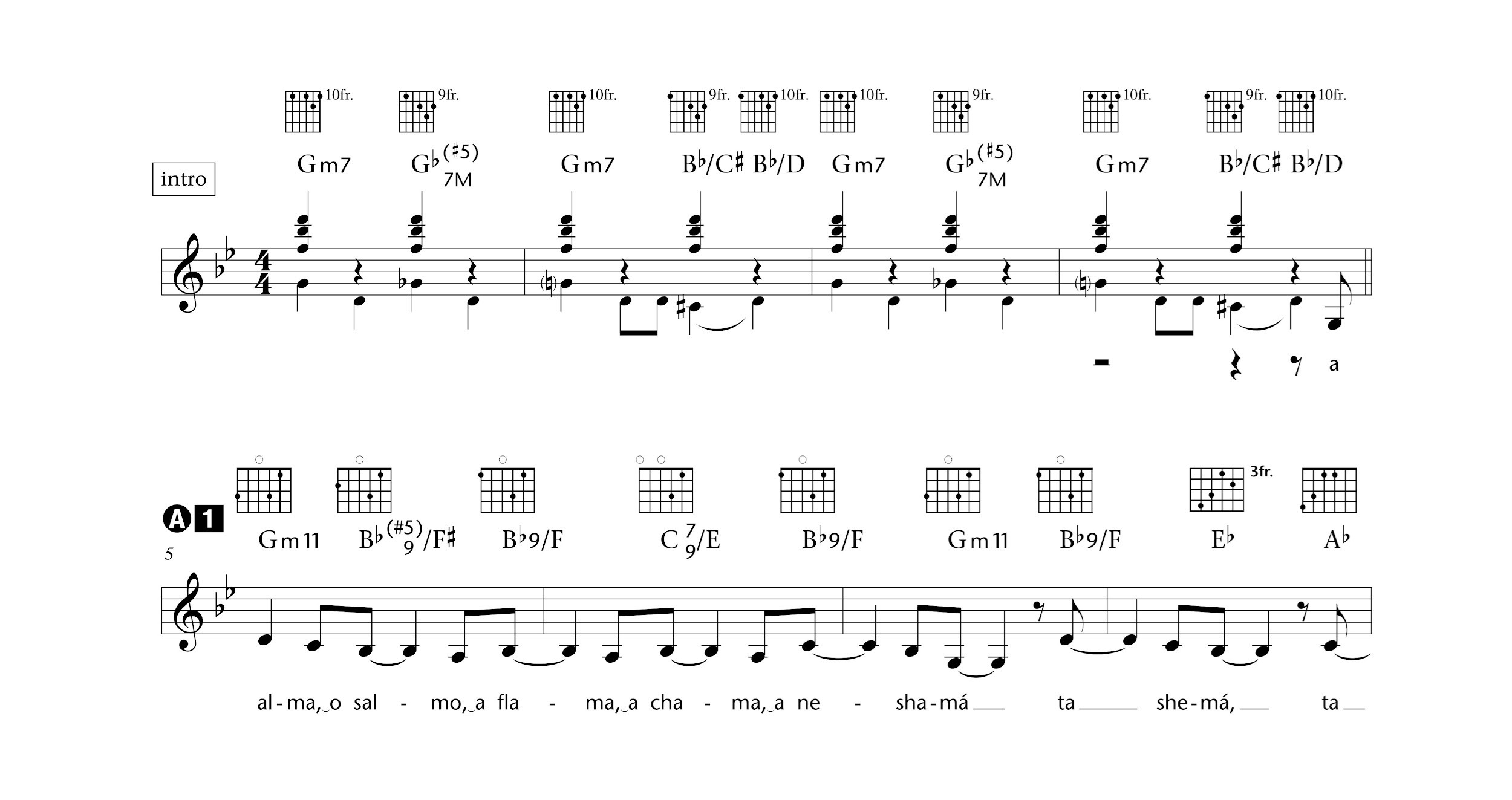

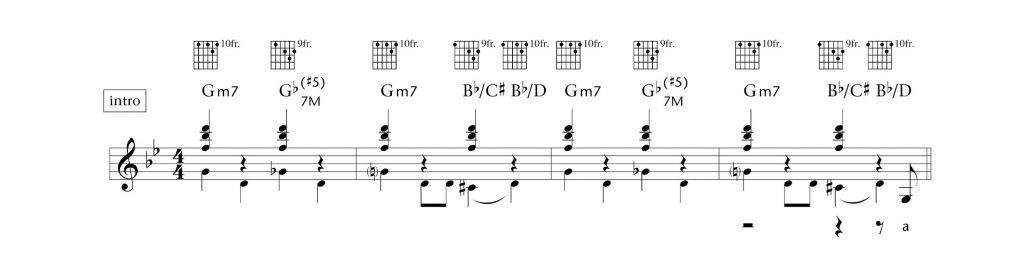

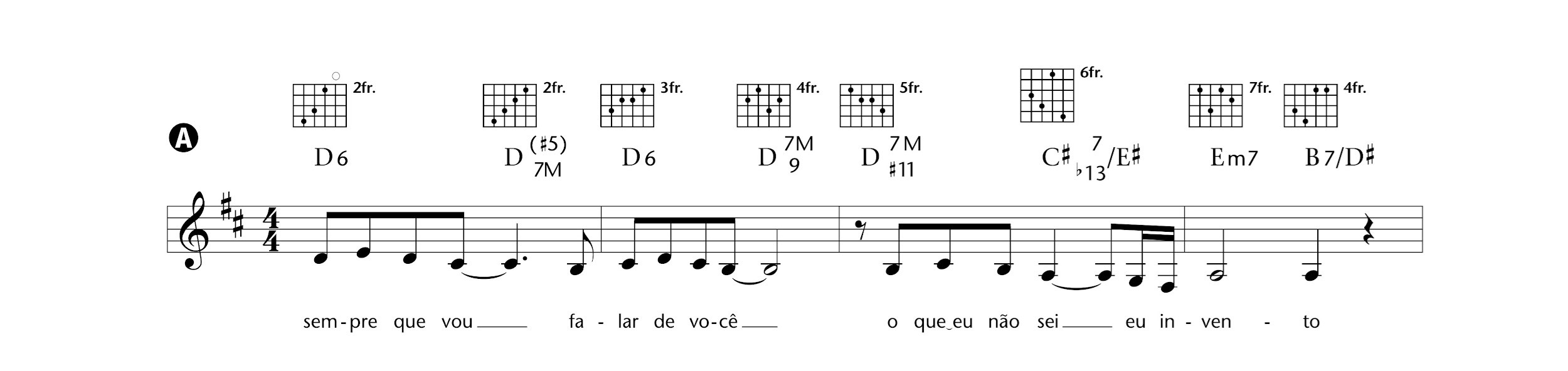

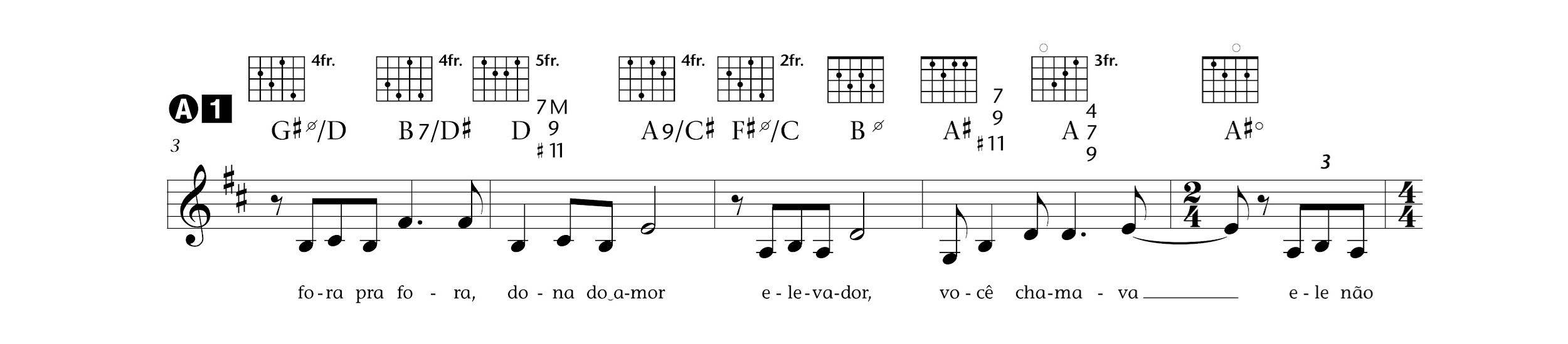

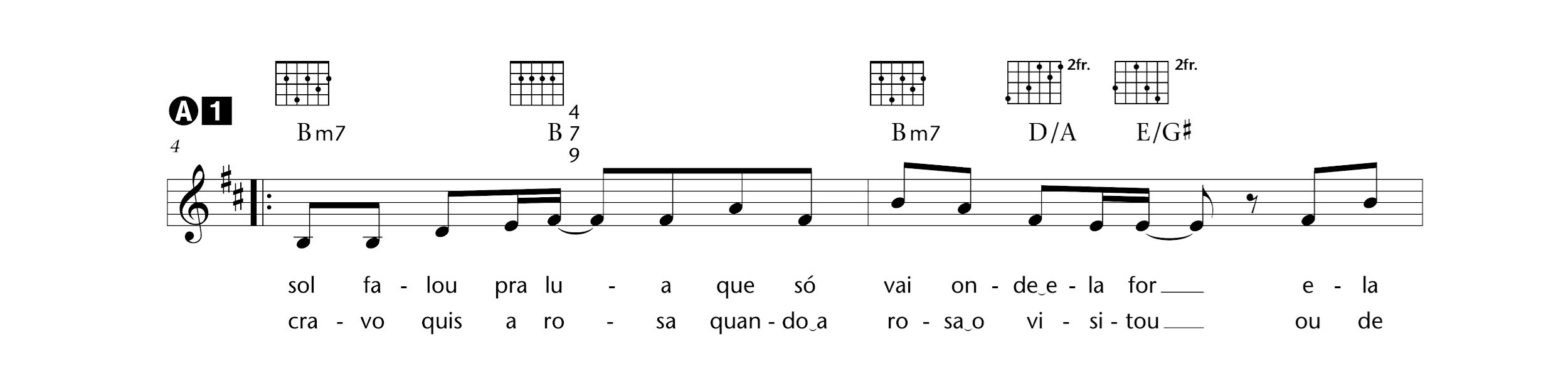

Released a decade after the first album, Ta Shemá (2008) is my favourite from the discography on offer. (I cannot tell if it is due to the coincidenc of being the first to hear it.) An album of arrangers, as the composer modestly puts it, featuring five of the best Brazil has to offer: Lincoln Olivetti, Dori Caymmi, Jacques Morelenbaum, Luiz Brasil and André Mehmari. The variety of the compositions was reflected in the choice of the arrangers and in the arrangements they produced. The standout arrangement and song, in my opinion, is Ta Shemá, the song that lends its name to the album. It could also have been Elevador, which explains just why producer Alê Siqueira calls Lafer, in the context of popular Brazilian music genre, “the Escher of harmony”.

Ta shemá, “come listen” in Aramaic, is the necessary call of these lyrics that are a fertile profusion of evocations and invocations used in religious festivals, especially Jewish ones. It is about an exceptional case in this discography, unique even, to my mind, where the musician’s faith is clearly the subject of a song; but, even here, the focus is not on preaching. Neither is it prescriptive, nor is it clearly delimiting: references such as the word “gibberish” make us question whether the meaning is generic – of overlapping voices (the “errant vowels”?) – or specific – how, in the Iberian Peninsula of the times of the Sephardic Diaspora, the accelerated Moorish speech was called. And, if it is specific, which includes the Arabs, the layers of meaning and interpretation are even greater and vaguer. If an interpretative template existed for the lyrics of this song, there is no question it would be one full of remissions. The overall impression I form is that of the main theme: come listen. The introduction’s rhythm sounds like the clapping of hands. A celebration? Certainly, a call. When dealing with complex texts like these, the call is: come listen again and again.

Independently of the interpretational complexity of the text, the phonemic construction is successful to the point that it can be enjoyed without even being able to tell what is transliteration or even without having the same deep historical and religious knowledge that I believe the author has. We know what this is. It is the pleasure of humming and listening a Nessun Dorma without understanding Italian or knowing about the libretto from the opera. We know it as the pleasure of phonemes and it transcends cultures.

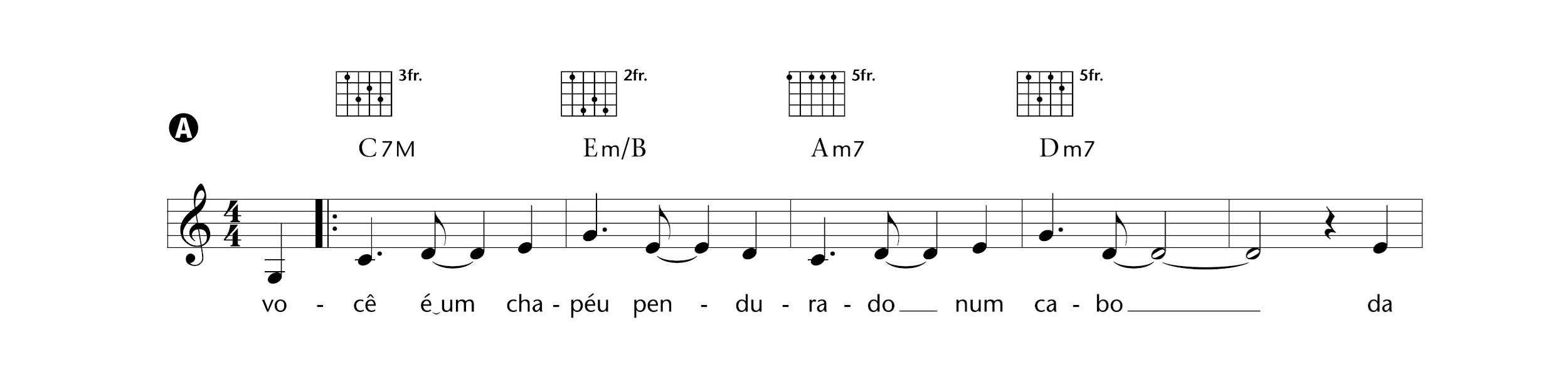

The music of Ta Shemá has a characteristic in common with many of Lafer’s songs, as well as those not by him: while the harmonic progressions are complex, the melody is simple. The majority of the melody takes place around the pentachord from the tonic to the perfect fifth. The call ta shema, happens within this tessitura and, more specifically, in the portion of the pentatonic scale it contains. In other words, the simpler the melody, the more complex the harmony and the greater the need to make the words heard. It is no coincidence that, when the melody leaves the boundaries of the fifth, it goes to the eighth, the note that will reaffirm the fundamental height, amplifying it. The majority of the song is in the eolic mode, which favors the sonority of the pentatonic scale, emphasized by the cadence of the seventh degree of the minor scale for the tonic (F-G).

More highlights from the album Ta Shemá:

- Poesia e Prosa (Manu Lafer & Danilo Caymmi, sobre texto de Antônio Cândido de Mello e Souza)

- Versão Fiel (Manu Lafer &Luiz Tatit)

- Elevador

Vinheta Baiana [Vignette from Bahia]

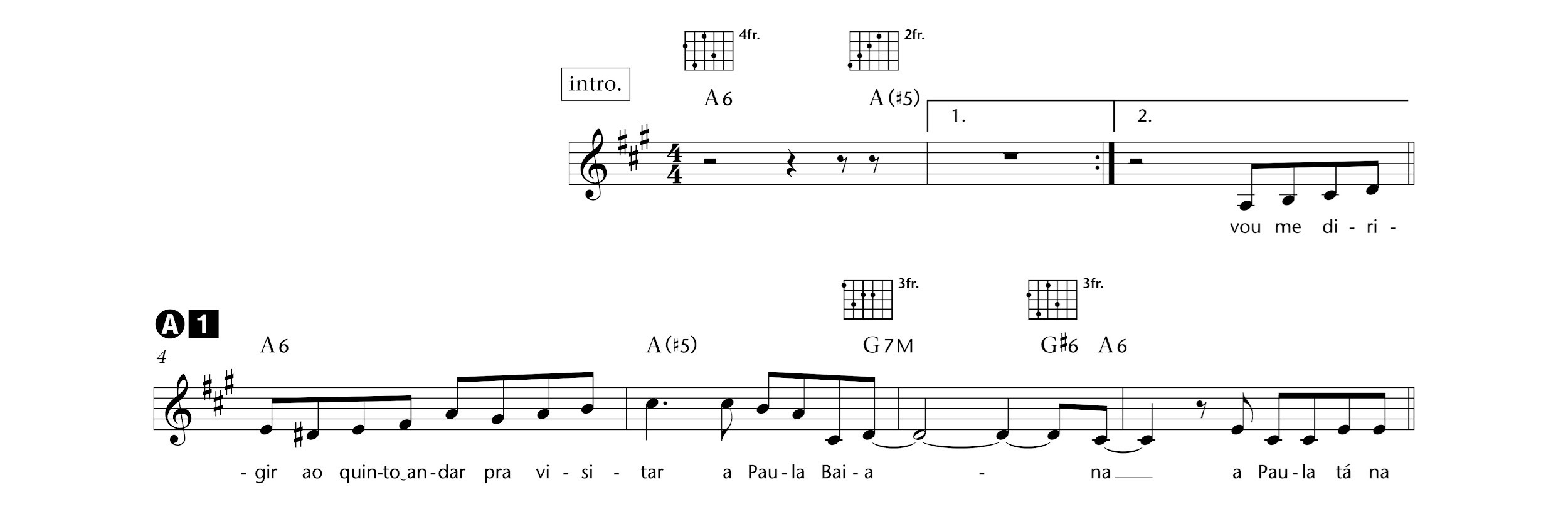

Vou me dirigir ao quinto andar pra visitar a Paula Baiana [I’m heading to the fifth floor to visit Paula Baiana]

A Paula tá na aula [Paula is in class]

Tá? Eu toco violão [Is she? I’ll play guitar]

Na toca de veludo mora dentro o violão [In the velvet burrow the guitar lives inside]

Se a gente abre [If we open it]

A mola joga fora o violão [The spring ejects the guitar]

A Paula me encolheu eu tô no ôco do caixão [Paula shrank me I’m inside the hollow coffin]

Vinheta Baiana, released in 2012, is the corollary of the objective I observe in the album Mané Mandou: in comparison to previous albums, in this one, Lafer seems, to me, to want to simplify the harmony in an attempt to simplify the songs as a whole (with the clear exception being Um Abraço no Pizza, a dense, instrumental piece dedicated to the musician couple John Pizzarelli and Jessica Molaskey, or the American Pizzarelli family of musicians, whose most well-known member is Bucky Pizzarelli). The constant among the other albums was to drip simplicity into turbulent waters; in Mané Mandou, it is the opposite.

Named a vignette, in a direct allusion to its brevity and – though this is my speculation – in an indirect allusion to its radiophonic style, the form lasts long enough. There is nothing missing: parts A, each of which have four bars, flank the eight-bar part B. Parts A are scalar; B features an alternating jumps in third compensated by movements in second. Both parts lead to the third of tonality, which gives the melody a scintillating nature, lively and with its own gallantry, in addition to setting the perfect school scene so well.

There is the temptation to classify Vinheta Baiana as a miniature song, considering its brevity: 22 bars that total 44 seconds. It would be a mistake: this is yet another song stripped of the repetitions typical of the form from which it comes; much less is it an aphorism of the musical form, a term Flo Menezes (1962) uses well in the book Apoteose de Schoenberg to classify that musical miniatures of Anton Webern (1883–1945), written in the context of the Second Viennese School (for example, the fourth from the Orchesterstücke, opus 10, satisfies itself with only six bars that last approximately 19 seconds).

More highlights from the album Mané Mandou:

- Rosas e Cravos

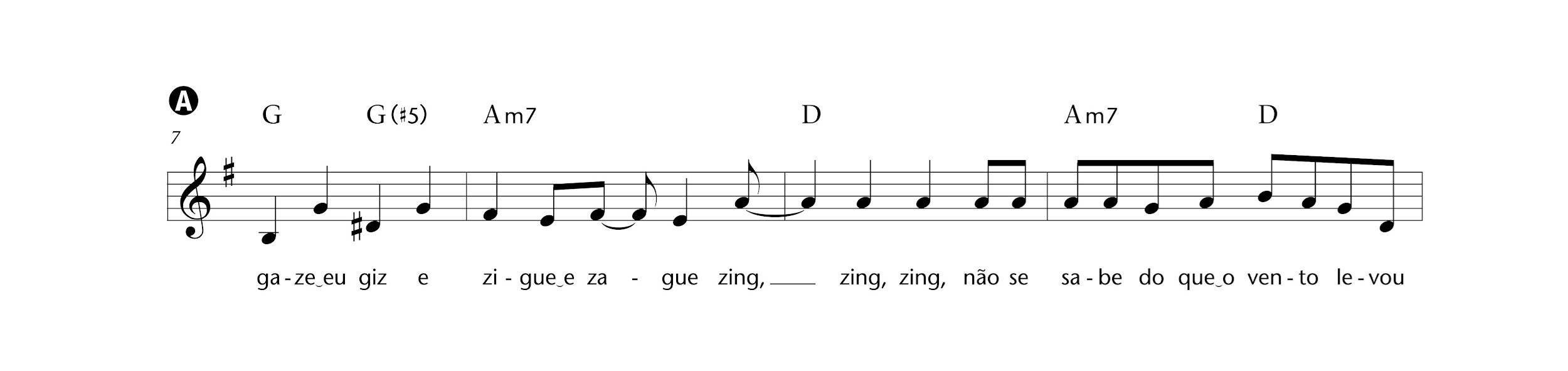

- Zing

- Um Abraço nos Pizza

Esmalteca [Varnish Factory]

Gabriela, Gabrielle, [Gabriela, Gabrielle,]

Misturinha até Paris [Cute mix until Paris]

Maçã do Amor, Final Feliz [Candy Apple, Happy Ending]

ah, Flamenca, Ah, Cigana, [ah, Flamingo, Ah, Gypsy

Ninfa, Dengo, Pôr-do-Sol [Nymph, Enchantment, Sunset]

um Videoclipe, um Tititi [a Videoclip, a Tweet-tweet-tweet]

Fio de Seda, Véu, [Silk String, Veil,]

Salomé, Frapê, [Salome, Frappé]

Prenda, Tafetá, Polar [Gift, Taffeta, Polar]

Areia ou Nova Era? [ Sand or New Era?]

Papaya, Canela, Tanga, Baunilha, [Papaya, Cinnamon, Thong, Vanilla,]

Neve, Neblina, Risque, Zazá [Snow, Fog, Risqué, Zaza]

essa Espera é Contigo [this Wait is With You]

quem vê Caras rói as mãos [who sees Faces chews their hands]

deixa Beijar, Obsessão [allow Kissing, Obsession]

Via Láctea, não dissolva, [Milky Way, don’t dissolve,]

Serenata é pra trocar, [Serenade is to exchange,]

gostar de Luxo e retirar [liking Luxury is withdrawing]

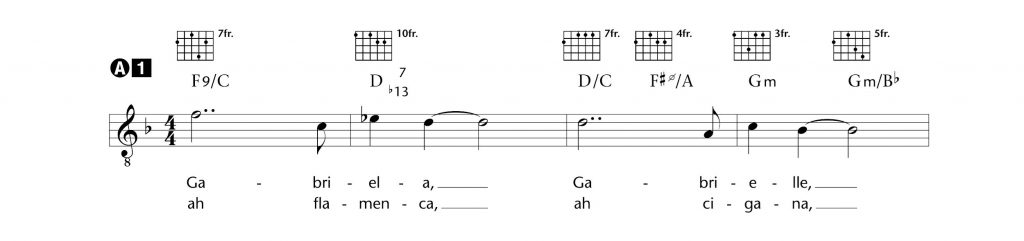

Using a kaleidoscope of words, Esmalteca belongs to the most atypical of Lafer’s albums, Canto Casual (2014): in it, the standards of the American songbook, which Lafer likes and is interested in, make themselves present and manifest, praising the jazz style. This album was released together with Someone Like Me, in which Lafer interprets standards.

Esmalteca uses the evocative, fun and picturesque names of nail varnish tones. They are (combinations of) words that seem to, at times, allude to, at others, narrate. It is a graceful female microcosm thatcould only have been told with a mix of reverence and curiosity. That explains the use of juxtaposition of words that are rarely or only casually connected. It is a frolic.

As regards the music, what calls attention is the recurrence of the polarization of the interval of the descending third that links parts A and part B.

More highlights from the album Canto Casual:

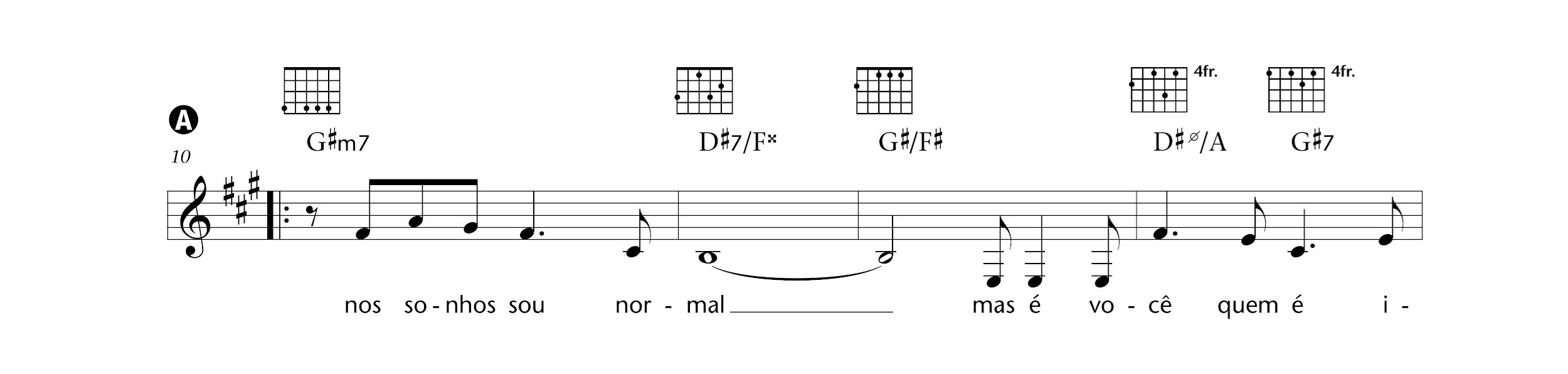

- Sonho Normal

- Céu e Chão

- O Milênio e o Minuto

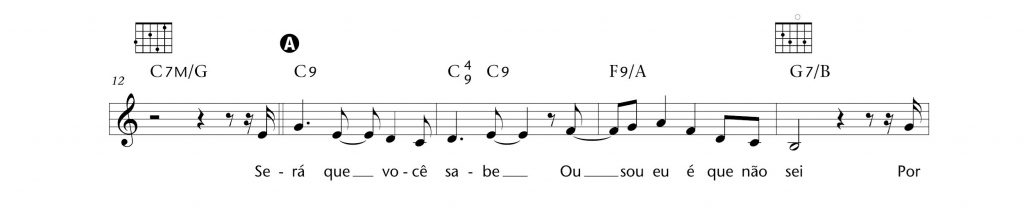

Ou Sou Eu [Or is it Me]

Será que você sabe [I wonder if you know]

Ou sou eu é que não sei [Or is it me that doesn’t know]

Por que acontece [Why this happens]

Que eu não posso mais viver sem você [That I can no longer live without you]

Um ano já passou, um mês a mais [Another year has passed, one more month]

Como no ano em que você nasceu [Like the year in which you were born]

Será que eu nasci também [Could I have been born too]

Antes de você me aparecer [Before you appeared to me]

Será que eu sabia viver [Could I have known how to live]

Antes de ouvir a tua voz [Before I heard your voice]

Antes de eu saber quem somos nós [Before I knew who we are]

Que a minha casa já morava [That my house already lived]

Tão vizinha ao coração [So close to the heart]

Todos os dias com o meu amor [Every day with my love] Pra você [For you]

Of a beautiful lyricism that, thanks to the Caymmi family, can be called Bahian, and not just because Ou Sou Eu was sung and played by Dori Caymmi. Dori plays the guitar throughout the album Um Lado Meu Que Você Não Conhece (2016) and also sings the reinterpretation of Samba de Uma Nota Só. The Caymmis are an influence and occasional partners for Lafer; Danilo Caymmi, a recurrent one. Like the album O Patriota, this is another clear example of mutual admiration.

In this song, the singer, in love, questions rhetorically and declaims knowledge of himself before the presence of his loved one (“could I have been born, too, before you appeared to me??”, “could I have known how to live, before I heard your voice?”). Such affection is sung by a beautiful, albeit contained, melody that emphasizes the intangibility of the muse. Circumscribed by the limit of the eighth, the voice rises almost only at the beginnings of the sessions and almost always on the word será, which is the future of the verb “to be” in Portuguese, and is also used to pose questions.

The harmony makes constant use of inversions of chords, which make the direct harmonic directions lighter. As light as this song. A testimony of the weight implicit in love.

More highlights from the album Um Lado Meu Que Você Não Conhece:

- Festiva (first released in the DVD A Lente do Homem, in 2008, and is also a highlight of this album)

- Você Já Sabe

- Retrato da Mulher Amada Bebendo Água de Madrugada

É um cavalo [It is a horse]

É um cavalo, é uma girafa [It is a horse, it is a giraffe]

É um cachorro, é uma vaca [It is a dog, it is a cow]

É capivara, é papagaia [It’s a capybara, it’s a parrot]

É andorinha, é uma só [It’s a swallow, it is just one]

É um elefante, é um bicho, é um hipopótamo [It is an elephant, it is an animal, it is a hippopotamus]

Rinoceronte, um monte de quati, senhor [Rhinoceros, a bunch of coatis, sir]

É uma zebra, é chimpanzé [It is a zebra, it’s a chimpanzee]

Aqui lagarta, ágora gralha [Here a lizard, now a passerine]

Alta montanha, homem cavá-la [High mountain, man digs there]

É criancinha, é sinhá só [It’s a child, it’s just ma’am]

É um canguru, é um salto de urubu bambu [It is a kangaroo, it is bamboo vulture hop]

É uma fonte, um tanque, um tanto de tatu [It is a spring, a tank, an amount of armadillos]

Eu não vejo o seu leão [I don’t see your lion]

Não estou vendo o seu pavão [I’m not seeing your peacock]

Que garça? Que situação! [What heron? What a situation!]

Chorar de jacaré [Crocodile tears]

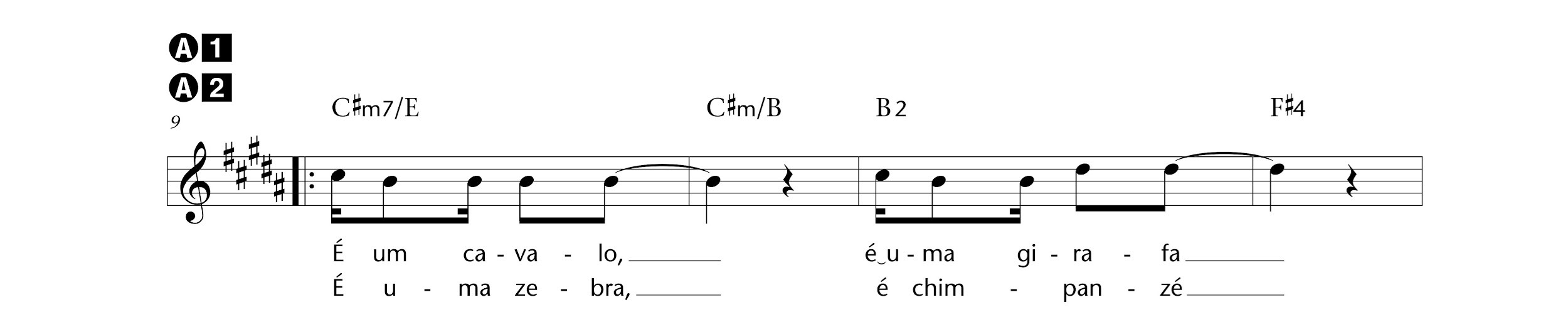

The fruit of a creative meeting between Lafer and Luiz Brasil (1954-), É Um Cavalo is one of the most natural of the songs in the album As Luas de Marte (2016). Brasil and Lafer got to know each other professionally through the album Ta Shemá, for which the former wrote three arrangements. As Luas de Marte is composed of songs for children… and their parents. A constant in albums of this kind is having to balance the interest that their songs pique in children and in their guardians; at the end of the day, it is the latter who make the final decisions on purchases and listening material. In this sense, too, the album is well made, because it transcends ages. At the moment in history where parents are less able to spend time with their children and where these children are raised based on YouTube and the recycling of folk songs, having Brasil and Lafer creating for the little ones is a breath of fresh air. There is even an instrumental piece in As Luas de Marte (Prelúdio para Beatriz)

músicos como Luiz e Manu criem para os pequenos. Até uma música instrumental há em As Luas de Marte (Prelúdio para Beatriz): God willing it is a point of entry for a generous genius like Schumann, expressed, for example, in his opus 68 and 118.

Sung by Karina Zeviani, who, with the exception of Propaganda and Estrada do Guri, is the singer throughout the album, É Um Cavalo emulates the way children point things out, in joy or surprise. It is the tone of interjection typical in the aurora of life, at the dawn of knowledge. It is what adults resent losing: the enthusiasm for discovery. Musically, it is divided into three parts, contrasted by the division of the rhythm. However, it is done without grand contrasts, rhythms or harmonies: the focus is on the lyrics.

More highlights from the album As Luas de Marte:

- O casamento da Centopéia

- Propaganda

- Estrada do Guri